Why Mental Health Treatment Doesn’t Work the Same Everywhere: A Cultural Perspective on Psychotherapy

When the Science of the Mind Forgets to Learn the Language of the Soul

Modern psychotherapy, as developed in the West, claims to speak the universal language of the human mind. But a recent study titled Culturally Sensitive Mental Health Research: A Scoping Review argues that this confidence might be misplaced. Psychological treatment rarely travels intact across cultural borders. What counts as “effective therapy” in New York or London can fail—or even backfire—in Tehran, Delhi, or Nairobi.

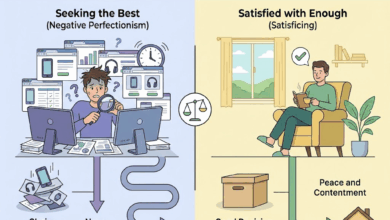

The researchers behind this review show that much of modern psychotherapy rests on Western assumptions about the individual, emotion, and communication. It assumes that a person is an autonomous being who seeks self-understanding through introspection. Yet in many parts of the world, the self is understood relationally: through family, community, and faith. A therapy built on radical individualism can easily lose its meaning where identity itself is collective.

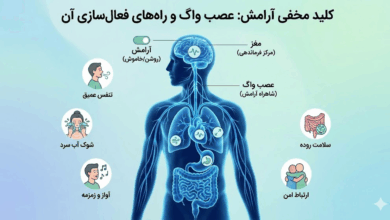

In cultures where emotional restraint signals maturity and social respect, therapies that rely on “expressing feelings openly” can feel inappropriate or even shameful. In places where mental distress carries social stigma, direct talk about depression or trauma can provoke resistance instead of healing. Therapists, therefore, must learn the cultural language of suffering; one that is often metaphorical, embodied, or poetic. In many non-Western societies, people describe their psychological pain not as “depression” or “anxiety” but as “a heaviness of the heart” or “fatigue of the soul.”

That is why the authors call for a true cultural translation of therapy; not just translating words, but translating experience. Concepts like “self-realization” or “authenticity” cannot be applied mechanically to contexts where selfhood is interwoven with duty, family, and spirituality. Western psychology grew out of a history that glorified independence; other traditions, by contrast, see well-being as harmony within a web of relationships.

The review also notes that therapists in developing countries often face a double bind: when they apply Western models without adaptation, they encounter mistrust from patients and dissonance within themselves. Many describe feeling more like cultural translators of imported psychology than practitioners rooted in their own traditions.

Still, the study points to hopeful developments. In Japan, the concept of ikigai (a sense of purpose) has entered therapy; in India, therapists draw on yoga and Ayurvedic principles to balance mind and body; in Iran, some counselors weave poetry and spiritual narratives into their sessions. These are not rejections of science but attempts to humanize it; to let local meaning shape the path to healing.

However, the authors caution against superficial “localization.” Simply adding cultural symbols without understanding the underlying worldview risks cosmetic diversity. Real adaptation requires deep empathy with how a society defines pain, shame, and recovery. For instance, a prayer, a conversation with a friend, or participation in community rituals may function as powerful therapeutic tools precisely because they align with cultural patterns of resilience.

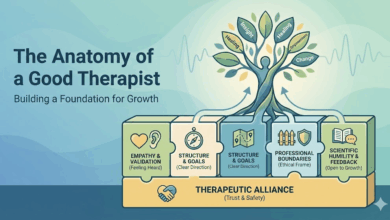

Ultimately, the study concludes that psychology cannot be truly global until it accepts that the mind is always local. Mental suffering is not just biochemical; it is narrative, historical, and cultural. An effective therapist must therefore be part scientist, part translator; someone who listens not only to what is said, but to the world from which it is spoken.

Global mental health will only thrive when it grows from within cultures rather than being imposed upon them. Therapy, in its deepest sense, begins when the science of the mind learns the language of the soul.

Source: BMC Psychiatry – Culturally Sensitive Mental Health Research: A Scoping Review