When Doing Nothing Becomes the Hardest Thing to Do

In a world that moves faster every day, even rest has turned into an obligation. We schedule relaxation, optimize mindfulness, and measure our downtime by productivity. But a new study, Leisure and Meaning in Life, reveals that mental well-being doesn’t come from simply having free time; it depends on how we use it.

Researchers asked hundreds of people across age groups to describe their leisure activities and rate their sense of meaning, satisfaction, and mental health. The results were striking: those who spent their free time in activities that created connection or purpose — like reading, learning something new, or spending time with friends — reported greater well-being. Meanwhile, people who devoted their leisure mainly to passive or screen-based consumption felt emptier and more anxious afterward.

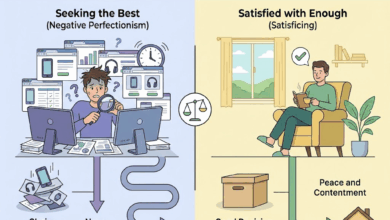

The study distinguishes between active and passive leisure. Active leisure engages the mind or body in something meaningful; passive leisure merely numbs us. Scrolling endlessly through social media may seem relaxing, but it drains mental energy and deepens fatigue. Paradoxically, the more stimulation we consume, the less restored we feel.

One of the most revealing findings is that meaningful leisure isn’t always fun. Activities like volunteering, caregiving, or creative work can be tiring but still deeply fulfilling, because they connect us to something larger than ourselves. Shallow pleasure, on the other hand, provides instant relief but no lasting satisfaction.

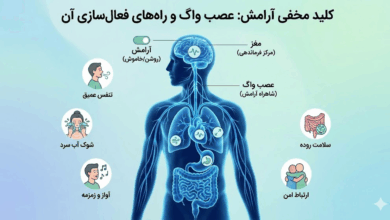

At the heart of this research lies a quiet insight: leisure only restores us when it brings us back to ourselves. Many participants said they felt most grounded during simple, mindful moments — walking aimlessly, painting, or listening to music without distraction. Psychologists call this state flow — when the mind is absorbed in the present and freed from the noise of time.

The digital era, however, has eroded this balance. We now have infinite access to distraction, and yet we’ve lost our capacity for boredom. The researchers argue that boredom isn’t an empty state; it’s the space where creativity and self-reflection emerge. When we fill every silent moment with a screen, we rob the mind of its chance to breathe.

The study also highlights how relationships during leisure matter more than duration. A short, meaningful conversation in person often nourishes more than hours spent chatting online. True rest, it seems, has less to do with time off and more to do with emotional presence.

In their conclusion, the authors write: “Leisure is not the absence of work ; it is the presence of self.” Rest isn’t what happens when work ends; it’s what begins when we remember who we are outside of productivity. Modern life may have given us the freedom to stop working, but not the ability to truly rest. To recover that, we must relearn how to be still; not online, but alive.

Perhaps leisure, like meaning itself, is a practice: a deliberate act of slowing down, of doing less but feeling more. In a world obsessed with movement, standing still may be the most radical form of self-care.

Source: PMC – Leisure and Meaning in Life