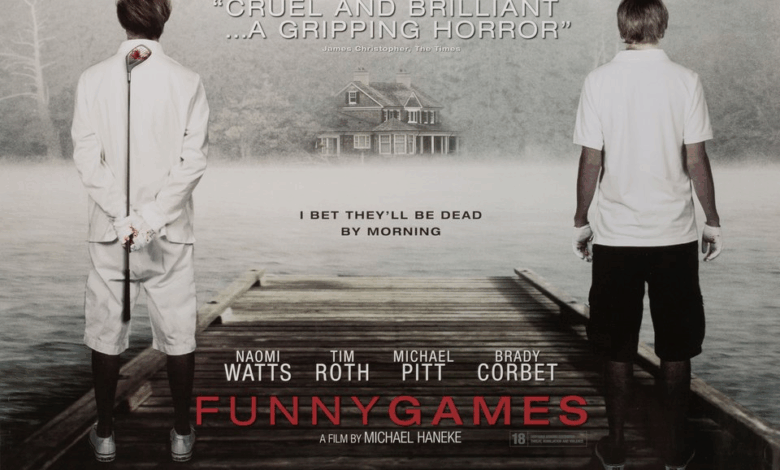

A Test of Enduring Suffering; Why Funny Games Wants You to Turn Off the TV But You Can't

Cinema is usually a refuge for escaping reality; a place where heroes triumph, justice is served, and the audience leaves the theater with a sense of satisfaction. However, with his 2007 shot-for-shot remake of his own earlier work, Funny Games, Michael Haneke proved once again that cinema can be a tool for psychological torture and for awakening the dormant conscience of the audience. This film is not a typical thriller; rather, it is an anti-violence manifesto that challenges the viewer by using violence itself. The story has a simple, almost cliché appearance: a wealthy family heads to their summer villa by the lake for a vacation, but their peace is turned into an absolute nightmare with the arrival of two polite, well-groomed young men wearing white gloves. What ensues is neither a robbery story nor a personal revenge tale, but a sadistic game in which “we,” as the audience, are the primary accused. We intend to examine why watching this film is so difficult yet deeply moving by focusing on its visual style, grueling suspense, and the psychology of violence.

One of the most brilliant and simultaneously disturbing aspects of Funny Games is its direction and cinematography. The filming and framing in this work are designed specifically to make the viewer deeply uncomfortable. Unlike Hollywood action or horror films where the camera is constantly shaking, moving, and changing angles to create false excitement, Darius Khondji’s camera in this film is often static, cold, and indifferent. The camera here plays the role of a ruthless observer that makes no effort to intervene or even sympathize with the victims. A significant portion of the physical violence happens off-screen. Haneke intelligently keeps the camera fixed on the face of the person witnessing the crime (or even on an empty wall), while the sounds of screams and blows are heard from outside the frame. This technique activates the imagination, as the audience’s mind always constructs an image more terrifying than what the camera can show; it also creates torment. When the camera zooms in on the suffering face of Naomi Watts and refuses to move, we are forced to stare at her pain for minutes. There are no cuts to give our eyes a rest. This prolonged stillness transfers a sense of suffocation and confinement to the viewer. The frames are arranged such that there is no visual escape; just as the characters have no way out of the house, we have no way out of these tight, static frames.

Suspense in cinema usually means waiting for an event to occur, accompanied by ominous music. But in Funny Games, the definition of suspense is different. Here, suspense means the continuation of suffering. There is no musical score to induce fear. Absolute silence rules the atmosphere, broken only by ambient sounds and the calm, polite dialogue of the attackers. This silence lends a terrifying realism to the film. The suspense is so intense that the characters’ bad feelings and hopelessness slowly infiltrate the viewer’s soul. As the audience, you are constantly waiting for the moment the tables turn. You wait for that cliché moment when the father suddenly unties the ropes and attacks the intruders, or the police arrive. But Haneke ruthlessly closes every single window of hope. This gradual despair creates a state of nausea and internal anxiety. We don’t feel the pain of breaking bones, but the pain of the characters’ helplessness and humiliation flows through our veins like poison. This sensation is so strong that it blurs the line between “film” and “reality” in the viewer’s mind, placing them in a position where it feels as if they, too, are sitting in that living room with their hands and feet bound.

Perhaps the strangest feeling while watching this piece is the intense desire to stop the film. The filmmaker deliberately brings us to a point where the audience no longer wants to sit and watch. This is not a flaw, but exactly the director’s goal. Haneke wants to force us to ask ourselves: “Why am I still watching?” The film is full of moments that question the cinematic logic of “entertainment.” The villains speak with politeness and decorum, yet their actions are savage. This contrast is indigestible for the viewer’s mind. When the torture is prolonged and no hero emerges, our instinct commands: “That’s enough, turn it off.” The peak of this psychological game is when the character “Paul” looks directly into the camera and winks at us or speaks to us. He asks, “Who are you betting on?” or “Do you still think they have a chance to win?” By breaking the fourth wall, Haneke pulls us out of the position of an “innocent spectator” and turns us into an “accomplice.” As long as we sit before the film, we are fueling this display of violence. Paul knows we are thirsty for blood and thrills, and he is performing this show for us. If we leave the cinema or turn off the TV, the show ends, and perhaps the family survives. But we stay, because we are curious. And it is this very curiosity that causes the bad feeling flowing through the film to penetrate directly into our conscience.

If we were to identify a single scene as the main reason why some audiences hate it and others consider it a masterpiece, it is the “Remote Control” sequence. In the moment when the woman finally succeeds in grabbing the gun and killing one of the attackers, the audience screams with joy. “Justice is finally served!” But suddenly, the other attacker picks up the TV remote control and rewinds the film. He pulls time back and prevents that event from happening. This is Haneke’s biggest slap in the face to the audience. He tells us: “This isn’t Hollywood. My rules allow no escape here. You are not supposed to taste the pleasure of victory.” This scene is exactly where many viewers, out of sheer anger and frustration, want to shut off the film. This moment is the perfect symbol of tormenting the viewer and playing with their expectations. The filmmaker shows us that we are captives in his hands and have no control over our own emotions.

Funny Games (۲۰۰۷) is not an enjoyable cinematic experience; rather, it is a necessary one. This film is like a bitter medicine prescribed to treat the disease of “desensitization to violence.” By combining static and disturbing framing, eliminating music, creating a suspense that eats away at the soul like a parasite, and finally by removing the audience’s desire to continue watching, Haneke has created an unforgettable work. This film reminds us that real violence is neither exciting nor entertaining; it is ugly, painful, and endless. If you felt anger, depression, and revulsion after watching the film, congratulations; you have received the exact message Michael Haneke put in the bottle for you. This film was made to disturb you, and in doing so, it is one of the most successful works in the history of cinema.