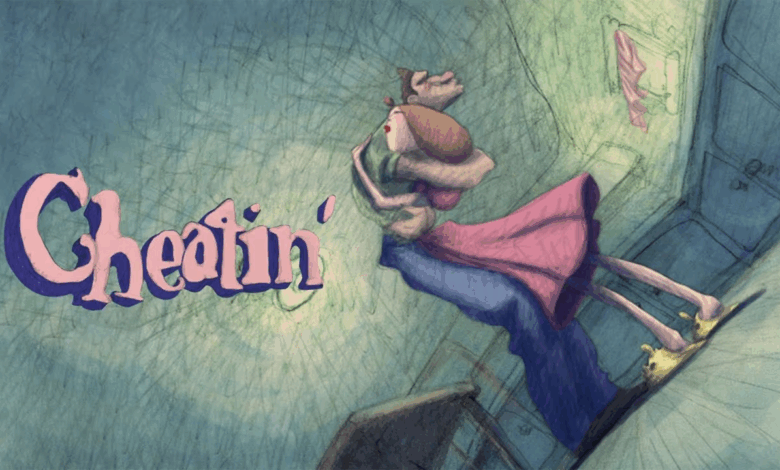

Cheatin’

Love, Obsession, and Madness Rendered in Boiling Color and Sharp Wit

An essay on Bill Plympton’s hand-drawn feature: craft, psychology, influences, and reception

If jealousy, desire, and fantasy could be poured into a single, boiling canvas, the result might look like

Cheatin’. On the surface it is a story about infidelity; underneath, it is a fever-dream about the mind in love,

a darkly comic parable where bodies stretch, melt, collide, and reform with the logic of emotion rather than physics.

Bill Plympton’s feature is at once funny, aching, and unashamedly strange—an adult animation that replaces dialogue with

gesture and turns raw feeling into motion.

Premise in Brief

A chance encounter binds Ella and Jake in a swooning, headlong romance. Marriage follows,

then a fatal misunderstanding: Jake becomes convinced Ella has betrayed him. Ella, desperate to win him back,

discovers a madcap machine that lets her slip into other women’s bodies, trying on identities the way someone might

try on dresses, and staging elaborate attempts to reclaim a love curdled by suspicion. The plot is simple by design,

a springboard for visual invention and a study of how imagination can rescue and ruin us in the same breath.

Hand-Drawn to the Core

Plympton draws his films by hand, frame by frame. You can feel the graphite in every line, the human tremor in every

contour. Cheatin’ is constructed from thousands of pencil drawings washed with saturated color:

bruised purples, feverish reds, tobacco browns. Forms are elastic, never fixed. Limbs elongate and recoil; faces liquefy

into masks of envy or rapture. This plasticity is not a gimmick—it is the film’s psychology. Love, as depicted here,

does not sit still; it swells, distorts, and devours.

The shot design embraces theatrical framing and bold, poster-like compositions. Plympton cuts on emotion, not geography.

Edits accelerate when jealousy spirals; they lengthen when Ella regathers her resolve. Because there is almost no spoken dialogue,

the animation must “speak” on its own. It does so through timing, squash-and-stretch, and a choreography of looks and

touches that makes inner weather visible.

Color, Music, and the Pulse of Humor

Color in Cheatin’ operates like a mood ring. Scenes of infatuation pulse with warm, velvety tones; suspicion

brings in sickly greens; despair leaches saturation from the world. The score glides between sultry motifs and melancholic

interludes, underscoring the film’s swing from farce to heartbreak. When the music drops out, the scratch of pencil, the sigh of air,

the thump of a heartbeat fill the silence; it is physical comedy tuned to the key of longing.

The humor is primarily visual and often deliciously wicked: a Rube Goldberg procession of misunderstandings; a body-swap

sequence that literalizes the fantasy of becoming “the ideal woman” a jealous imagination invents; a carnival of erotic

exaggerations that lampoon macho delusions and romantic clichés at once. You laugh, then notice the bruise.

Psychology of a Fever Dream

Plympton is not moralizing about fidelity; he is dissecting obsession. The film suggests that what corrodes Ella and Jake

is less an act than an image—an internal hallucination that grows teeth. Jealousy hates ambiguity, so it manufactures

certainty. In that sense, Cheatin’ maps how the mind, terrified of the unknown, will choose a nightmare over a question mark.

From a psychoanalytic angle, Ella is propelled by eros, a life-drive that keeps inventing forms to keep love alive,

while Jake succumbs to thanatos, a deathly pull toward self-sabotage and control. Their dance is comic and tragic:

two people fighting not just each other, but their own projections. Ella’s surreal body-hopping becomes a metaphor for

the pressure to become everyone at once—the mother, the muse, the fantasy—until her sense of self thins to transparency.

The hard lesson the film finally proposes is simple and unsentimental:

love cannot be engineered through disguise; it demands the risk of being seen as you are.

Bill Plympton in Context

Bill Plympton, born in 1946, is the great holdout of American indie animation: a one-man studio whose signatures

are unmistakable—penciled linework, elastic anatomy, erotic absurdism, and a tone that mingles tenderness with

a slapstick cruelty only the heart can authorize. His career is punctuated by festival laurels and cult devotion,

not corporate franchises.

- Your Face (۱۹۸۷) earned an Academy Award nomination with a crooner’s visage mutating to match his warbling voice.

- I Married a Strange Person! (۱۹۹۷) turns newlywed bliss into a cosmic power trip about wish-fulfillment and its fallout.

- Mutant Aliens (۲۰۰۱) skewers propaganda and predatory hero myths with delirious glee.

- Idiots and Angels (۲۰۰۸) follows a bruiser who grows wings he does not deserve, a parable about reluctant grace.

Compared with these, Cheatin’ feels especially intimate. It sharpens his lifelong themes—desire as cartoon physics,

cruelty as a comic reflex—into a chamber piece about trust and identity.

Kinships and Counterpoints

Viewers who respond to Cheatin’ often find kinship in other artist-driven animations that put feeling before polish:

the hand-painted poignancy of Loving Vincent, the existential hush of Anomalisa, the psychedelic allegory of

Fantastic Planet, or the autobiographical bite of Persepolis. What sets Plympton apart is his comic savagery:

he pushes bodies past dignity until emotion spills out, then lets the tenderness seep back in.

Critics and Laurels

On the festival circuit, Cheatin’ drew sustained applause for its audacity and craft. Trade outlets praised the

film’s “carnival of imagination” and the muscular clarity of its hand-drawn style. Indie critics highlighted how the

absence of dialogue becomes an advantage: without words to explain or excuse, desire and suspicion must be drawn,

and drawing, here, tells the harder truth. While some viewers found its intensity exhausting, even dissenting reviews

conceded the power of Plympton’s vision and the singularity of his voice.

Why the Comedy Hurts

The laughter in Cheatin’ is not anesthetic. It is the laughter you use when the alternative is to flinch.

Plympton’s gags punch up at our worst impulses—ownership disguised as love, voyeurism dressed as concern, nostalgia used as a weapon.

By staging these reflexes as elastic spectacle, he lets us see their shape. Once you have seen it, it is harder to pretend.

Conclusion

The subject of Cheatin’ is familiar: love destabilized by doubt. Its treatment is anything but.

With nothing but pencils, paint, and a predatory eye for emotional truth, Bill Plympton builds a world where

longing is physics and jealousy is weather. The film’s humor is sharp, its imagery indecently alive, its empathy

unembarrassed. It asks a bracing question beneath all the farce:

what are we willing to become to keep a fantasy intact—and what does it cost when we try?

In the end, Plympton refuses tidy consolation. What Ella reaches for cannot be reclaimed by performance,

and what Jake fears cannot be mastered by suspicion. The film’s final grace lies in its honesty:

love is not a costume change; it is the hazard of being known. That is the joke, and the wound, and the reason

this wild little movie lingers long after its last, smoldering frame.