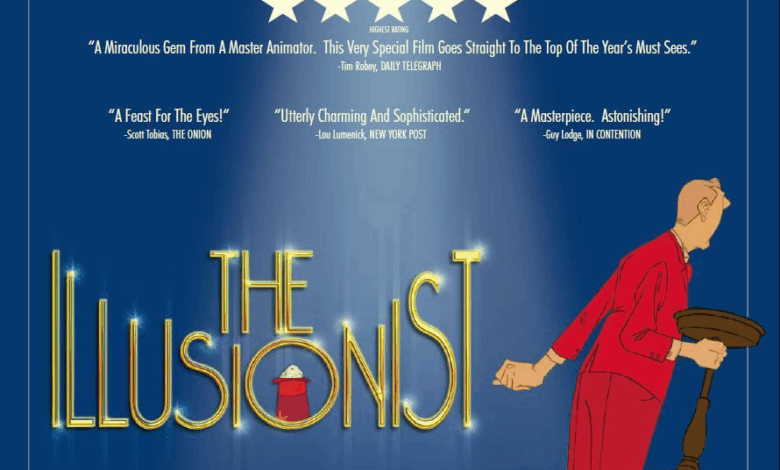

The Illusionist, A Magic Fading in the Dust of Time

When The Illusionist ends, a strange silence remains. It is not sadness exactly, nor joy, but something between the two — a quiet ache, a sense of acceptance. This animated film, directed by Sylvain Chomet and based on an unproduced script by Jacques Tati, is not about spectacle or laughter. It is about disappearance. About what happens when the audience leaves, and the performer is left alone on the stage.

It is a film that refuses to entertain in the usual sense. Its rhythm is slow, its tone subdued, its world washed in gray. Yet, beneath its quiet surface, it delivers a blow of truth straight to the heart.

Origins and Background

Released in 2010, The Illusionist was adapted from a script that Tati wrote in the 1950s, possibly as a letter to his estranged daughter. Chomet, known for The Triplets of Belleville, turned it into a hand-drawn elegy for both the artist and the act of performing itself.

The story follows an aging magician whose career is fading as the era of live entertainment gives way to television and pop music. Traveling across Europe in search of work, he meets a young girl named Alice in a remote Scottish village. To her, his tricks are real magic. She follows him to Edinburgh, where they live together for a while — he trying to maintain the illusion of success, she believing in it with innocent faith. But as reality creeps in, both are forced to face what illusion really means.

Artistic and Technical Aspects

Visual Style

The animation is entirely hand-drawn, using watercolored backgrounds and gentle lines. Every frame looks like a painting, evoking the melancholy of European streets under the rain. Chomet’s color palette — muted blues, grays, and browns — gives the film a nostalgic, almost ghostly texture. Nothing glows, yet everything feels alive.

The depiction of Edinburgh, with its cobblestone alleys, wet pavements, and neon lights, mirrors the magician’s emotional state. The more he struggles to keep performing, the colder and emptier his surroundings become.

Movement and Rhythm

The film is almost wordless. Dialogue is minimal, replaced by gestures, glances, and sound. This near-silent storytelling connects directly to Tati’s tradition of physical comedy and observation. Every small movement carries meaning; a tilt of the head or a tired shrug becomes a sentence.

The slow pacing is deliberate. Chomet wants us to sit in stillness — to feel time passing, to notice the details of loss. The slowness reflects the magician’s own rhythm: a man out of step with the modern world, still performing as if someone were watching.

Sound and Music

Music takes the place of dialogue. Composed by Chomet himself, the score combines piano and accordion melodies with moments of near silence. The sound of footsteps, the creak of a door, or the hiss of wind through narrow streets become part of the emotional landscape. In a world where language fails, sound becomes memory.

Psychological Depth

On the surface, The Illusionist is a story about aging and obsolescence. But psychologically, it is about projection — about how people fill their loneliness with illusions of each other.

The magician needs to feel useful, so he performs for Alice as if his tricks were real. Alice, young and poor, needs to believe in magic, so she accepts his kindness as proof that miracles still exist. They are not truly father and daughter, nor lovers; they are two souls using each other as mirrors for what they have lost.

From a psychological standpoint, the film reflects humanity’s desperate need to be seen. The magician performs not to impress but to exist. His stage is his identity. When the audience disappears, so does he. Alice represents that younger self — the hopeful, naïve belief that love and magic can last forever. Together they form a fragile illusion, sustained by kindness and denial.

Loneliness and Acceptance

In Jungian terms, both characters are engaged in a dance of projection. The magician sees in Alice the innocence he has lost. Alice sees in him the stability she craves. But illusions cannot last. As she grows up and falls in love with a young man, she no longer needs the magician. And he, realizing this, lets her go.

The final scene — the note he leaves behind reading “Magicians do not exist” — is both devastating and liberating. It marks the moment when he finally accepts reality, shedding the mask that has defined him. The illusion dies, but truth remains.

Symbolism and Themes

The magician stands for the artist, struggling to remain relevant in a world that no longer values his craft. The film’s background — empty theaters, silent streets, forgotten performers — becomes a metaphor for the fading role of art in modern life.

But it is also a meditation on aging. The magician’s body slows down; his audience moves on. The spotlight that once defined him now feels like a burden. His journey mirrors the universal human realization that we cannot remain who we were forever.

In the end, his decision to stop pretending is not defeat but enlightenment. It is the psychological stage Jung described as individuation — the acceptance of one’s limits and the reconciliation with one’s shadow.

Cinematic Minimalism

Among modern animated films, The Illusionist is unique for its restraint. It avoids dialogue, exposition, and even emotional manipulation. Instead, it trusts the viewer to interpret silence. Its minimalism is not emptiness but confidence.

Editing plays a subtle role here. Chomet allows moments to breathe, resisting the temptation to cut quickly. Each shot lingers long enough for emotion to unfold naturally. This measured rhythm mirrors the slow erosion of illusion itself.

The lighting, too, supports the theme: the colder tones dominate the present, while warmer hues appear only in brief flashes of hope or memory. The entire visual design is, in effect, a portrait of time fading away.

The Final Blow

When the magician walks away and Alice finds his note, the film reaches its quiet climax. There is no music swell, no catharsis — just the soft, inevitable truth that magic, like childhood, cannot last forever.

The audience might expect reconciliation, but Chomet denies that comfort. Instead, he offers honesty. The ending hits hard not because it surprises, but because it feels like a truth we already knew but refused to face.

“The Illusionist” is not meant to console; it is meant to awaken. It reminds us that beauty lies in impermanence, that illusions are only painful when we refuse to let them go.

Yes, the film is slow. Yes, it is melancholic. But in its quiet sorrow, there is profound grace.

It is a story not of loss, but of acceptance — of taking responsibility for our own illusions and finding dignity in letting them dissolve.

That, in the end, is its real magic: the courage to accept the end of magic itself.