Why the most imaginative work by the author of Slaughterhouse-Five is actually his most terrifying prediction for humanity.

If “Slaughterhouse-Five” was Kurt Vonnegut’s primal scream against the fire of war, “Cat’s Cradle” is his bitter, frozen sneer at human stupidity, science without conscience, and the comfort of false religions. For those devoted to Vonnegut’s unique voice – who have appreciated his candid thoughts in “A Man Without a Country” or his grapple with determinism in “Timequake” – reading “Cat’s Cradle” offers a distinct experience. It is akin to watching a magician who, instead of pulling a rabbit out of a hat, casually reveals the end of the world. As you rightly observed, this is perhaps his most imaginative and metaphorical work, yet lurking beneath the sci-fi surface are the most horrifying realities of the 20th century.

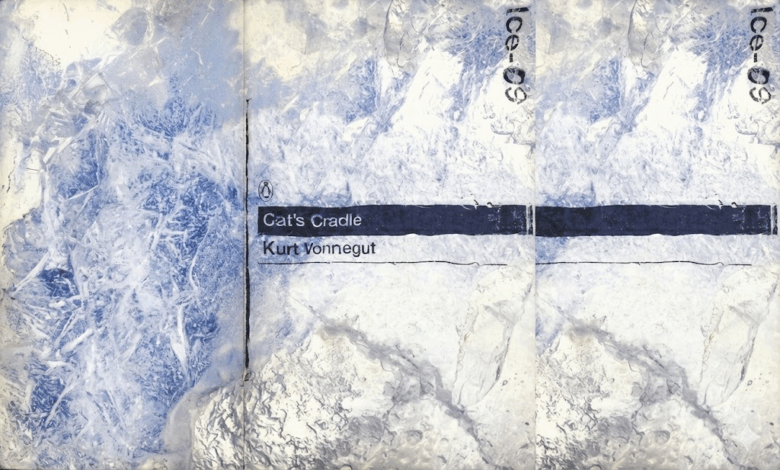

Ice-Nine: A Chilling Metaphor for Science Without Conscience

In this novel, Vonnegut elevates the art of metaphor to a terrifying new level. While Slaughterhouse-Five dealt with the firebombing of Dresden that turned a city to ash, here the threat is the exact opposite: Freezing. The plot revolves around a fictional substance called “Ice-Nine,” created by Dr. Felix Hoenikker (a caricature of the father of the atomic bomb).

Hoenikker represents a recurring archetype in Vonnegut’s universe: the scientist who plays with the fundamental forces of the universe like a “child genius,” utterly indifferent to moral consequences. For Hoenikker, freezing the world’s oceans is merely an interesting puzzle to solve. This brilliant metaphor illustrates how the world is often pushed toward destruction not by evil villains, but by intelligent, indifferent men.

A Cradle with No Cat: The Philosophy of Emptiness

The novel’s title is perhaps its most profound philosophical statement. “Cat’s Cradle” refers to a string game played with hands. One of the characters, observing the game, remarks: “No wonder kids grow up crazy. A cat’s cradle is nothing but a bunch of X’s between somebody’s hands, and little kids look and look and look at all those X’s… No damn cat, and no damn cradle.”

This is Vonnegut’s manifesto regarding human structures. Politics, national borders, scientific accolades, and even nations are all just like the cat’s cradle: invisible lines we have spun around ourselves and agreed to believe in, but which are, in cosmic reality, empty and absurd. Vonnegut uses his signature dark humor to show us playing with invisible strings while the world stands on the precipice of ruin.

Bokononism: The Sanctity of Bittersweet Lies

Alongside his critique of science, Vonnegut dismantles religion through the creation of “Bokononism.” The opening line of this fictional religion’s holy book is a masterpiece of irony: “All of the true things I am about to tell you are shameless lies.”

In the bleak world Vonnegut constructs, the truth (like Ice-Nine) is cold and lethal. Therefore, humanity needs “harmless untruths” (which he calls foma) to survive. If “Timequake” was about the exhaustion of repetition, “Cat’s Cradle” is about the necessity of illusion to endure reality.

Vonnegut vs. Vonnegut: Where Does This Book Stand?

For a reader familiar with “Slaughterhouse-Five,” “A Man Without a Country,” and “Timequake,” this novel serves as a crucial piece of the puzzle:

- Compared to Slaughterhouse-Five: While Slaughterhouse was deeply personal, rooted in Vonnegut’s own trauma as a POW, Cat’s Cradle is global. It doesn’t just critique a war; it critiques the entire foundation of modern civilization.

- Compared to A Man Without a Country: Everything Vonnegut stated directly as political essays and commentary in A Man Without a Country is dressed here in the garb of fiction. The anger is the same, but the delivery is more theatrical.

- Compared to Timequake: If Timequake was the product of an older author weary of fate, Cat’s Cradle buzzes with the wild energy and creative risk-taking of Vonnegut in his prime.

Conclusion: Laughing into the Abyss

“Cat’s Cradle” remains a masterpiece of dark satire. It teaches us that the apocalypse might not arrive with a Hollywood-style explosion, but through a simple act of clumsiness, a childish prank, or a frozen grin. Vonnegut leaves his reader with a singular, powerful lesson: when we have no control over the madness of the world, perhaps the only weapon left is to laugh at the emptiness of the cradle.