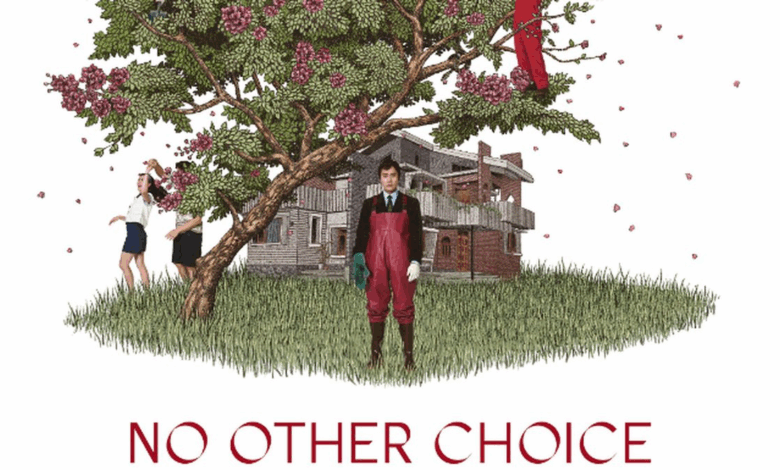

وقتی پدر برای نان شب آدم میکشد؛ چرا «هیچ انتخاب دیگری نیست» ترسناکترین فیلم سال است؟

A Comprehensive Review of “No Other Choice”; A Symphony of Violence, Love, and Survival in Park Chan-wook’s New Masterpiece Viral Title: When a Father Kills for Bread; Why “No Other Choice” Is the Scariest Film of the Year

In the history of cinema, there are rare moments when an auteur filmmaker, after years of experience and creating genre-defining works, decides to gather all their technical and philosophical knowledge into a single entity; a work that bears their personal signature while resembling none of their previous films. “No Other Choice” holds precisely such a position in the brilliant filmography of Park Chan-wook. The director, whom the cinematic world recognizes for poetic violence, obsessive framing, and bloody revenge tales of the Vengeance Trilogy—especially his immortal masterpiece, Oldboy—has this time turned his camera not toward a solitary confinement cell with bizarre wallpaper or a fantastical asylum, but toward the scariest possible place in the modern world: the job market and career security. This film, a free and creative adaptation of Donald Westlake’s novel The Ax, is a wild concoction of black comedy, breathtaking crime thriller, bitter family drama, and biting romance that ruthlessly slams the dilemma of contemporary man onto the table. In this work, utilizing brilliant stars of Korean cinema, Park Chan-wook has created a narrative where “survival” is no longer a natural biological instinct, but a bloody, calculated managerial decision.

The story revolves around the character of Man-soo, played by a stunning Lee Byung-hun; an actor who had previously proven his ability in complex roles in works like Squid Game and I Saw the Devil, but here pushes the boundaries of acting further. Man-soo is a man whose entire definition of life is summarized by his job; he is an exemplary employee, a devoted father, and an ideal husband who has dedicated years of his life to a paper company. But when the ruthless wheels of capitalism turn and layoffs arrive, he suddenly finds himself in an absolute void. His firing is not merely the loss of a monthly income; it signifies the complete collapse of his identity and social standing. With exemplary skill and a rhythm that never loses its breath, Park Chan-wook charts the process of an ordinary, respectable man transforming into a cold-blooded killer. Unlike the character of Oh Dae-su in Oldboy, who resorted to violence for personal revenge, discovering the truth, and answering a philosophical question, Man-soo fights for something much more banal yet vital: maintaining appearances and family survival. He decides that instead of healthy competition – which in today’s saturated world is practically a bitter joke – he will literally eliminate his job rivals. He finds the resumes of other applicants, evaluates them, and murders anyone who is more qualified. This plot idea is shocking and radical in itself, but what turns it into a masterpiece is the film’s unique tone. The film is neither a typical scary slasher nor a cliché tearjerking drama; rather, it is a strange potion of both, mixed with biting black humor. We are dealing with a killer who has no significant martial arts skills nor devises complex plans; he is a clumsy, anxious, and deeply human killer. This very contrast between the “horrific crime” and the “ridiculous execution” creates a grotesque atmosphere that keeps the audience suspended between laughter and horror.

To gain a deeper understanding of “No Other Choice,” one must take an analytical look at the evolutionary path of Park Chan-wook’s cinema. If in Oldboy, violence was a tool for redemption or revealing past sins, here violence is merely an “administrative solution” and an “economic necessity.” In Oldboy, the main character, played by the unforgettable Choi Min-sik, is imprisoned in a room for 15 years, and when he emerges, the whole world is summarized for him in one question: “Why?”. But in “No Other Choice,” the question “Why” does not exist; everyone knows why. Because the mortgage is overdue, because the daughter’s violin tuition must be paid, and because the wife shouldn’t worry about the future. This shift in approach from “Greek tragedy” to “capitalist realism” indicates the maturation of the director’s social gaze. He no longer sees the need to resort to complex revenge tales to justify violence. He tells us that in the twenty-first century, the scariest monsters aren’t those with long fangs living in basements; they are the ones sitting next to you on the subway, smiling, concealing an axe in their briefcase instead of a sandwich because they have “no other choice.” The reference to the film’s title here is key; the title “No Other Choice” is a grand moral disclaimer that Man-soo, and perhaps all of us, use every day to justify our decisions.

One of the main, undeniable pillars of the film’s success is its acting ensemble. Lee Byung-hun, in the role of Man-soo, delivers one of the most complex and layered performances of his career. He must simultaneously be a kind father worried about his dogs’ food and a ruthless killer strangling a rival in a parking lot. Lee Byung-hun’s art lies in never letting the audience hate him. We accompany him, we pity him, and in complete disbelief, we wish for him to succeed in his murders. This dangerous empathy is exactly the trap the director has set for the spectator. Alongside him, Son Ye-jin, whom global audiences remember from the popular series Crash Landing on You, has a brilliant and distinct presence as Man-soo’s wife. She is the symbol of what Man-soo is fighting for: stability, love, and family peace. Her nuanced performance immensely strengthens the dramatic and romantic layers of the film, giving a tragic dimension to Man-soo’s crimes. The chemistry between these two actors makes the audience believe that all this bloodshed is rooted in a deep, albeit twisted, love. Furthermore, the presence of other powerful actors such as Lee Sung-min and Park Hee-soon in supporting roles has enriched the film’s social texture, reminding us of the high quality of contemporary Korean acting. Another fascinating point for long-time fans is the subtle and overt references to the director’s previous works; it is as if the spirit of the explosive, manic performances of past works has been breathed into the body of this film, and Man-soo is the modern, ironed-out version of those scarred heroes who, this time, use other tools instead of a hammer to shatter the skull of reality.

Contrary to its crime-thriller, suspenseful exterior, “No Other Choice” is at its deepest layer a full-fledged, shocking family drama. The film precisely shows how an individual’s unemployment, like a devastating earthquake, shakes the very foundations of the family. Man-soo’s relationship with his wife, his attempt to maintain the heroic father figure image for his children, and the psychological pressures resulting from the shrinking table are depicted with miniature, precise details. The director intelligently juxtaposes warm, intimate family moments right next to cold, bloody sequences. This contrast makes the violence in the film feel more painful and tangible. When Man-soo returns home after a horrific murder and smilingly tells a story to his daughter, we witness the peak of modern human alienation. The film reminds us that the family, the most sacred social institution, can sometimes become the greatest motive for committing crime. Love in this film is not necessarily saving; it can be destructive—a love that compels a father to stain his hands with blood for the welfare of his children. This aspect of the film elevates it beyond a mere crime work into a sociological study of the family institution in the age of neoliberalism.

Park Chan-wook is always known as a master of form and imagery, and in this work too, he flaunts his artistry. His framing, like in his previous works such as The Handmaiden and Decision to Leave, is engineered and precise. But here, a type of controlled chaos is visible in the images, reflecting the disordered and collapsing mindset of the main character. The use of unusual camera angles, first-person (POV) shots from inside objects or from blind spots, and fluid camera movements that seem to slide on ice all serve to induce a sense of imbalance and vertigo. The film’s color grading is also noteworthy; the use of cold, gray, and metallic colors in work and urban environments contrasts with the warm, cozy colors of the home environment, highlighting the battle between the “outer world” and the “inner world.” One of the film’s most brilliant visual techniques is the manner in which murders are depicted. Unlike the usual Hollywood procedure that glorifies violence, making it fast or exciting, Park Chan-wook portrays violence here as “hard,” “dirty,” and “ugly.” Killing a human being in this film is not an easy task; it is full of trouble, messiness, resistance from the victim, and unwanted moments. This realistic approach within a fantastical form produces a black humor reminiscent of the Coen brothers’ works, but with the distinct, ruthless signature of Korean cinema.

“No Other Choice” is, beyond its story and characters, a sharp political and social manifesto. The film critiques a society where human value is measured solely by the digits on their paycheck. In a world where Artificial Intelligence and automation swallow more jobs every day, humans feel they have turned into disposable trash. Man-soo rebels against this system, but his rebellion is blind and misguided. Instead of fighting the system and employers, he fights other victims and his peers. This is the tragedy of the working and middle class fighting each other to seize the scraps of the capitalist table. The film delicately shows how the corporate system has redefined morality. Loyalty, hard work, and honesty, which were once considered virtues, have now become weaknesses. In this concrete jungle, only those survive who are willing to do “anything” and leave their conscience at the company door. Ultimately, “No Other Choice” is a film that will not let you go. You might laugh at comic situations during watching it, but this laughter will stick in your throat. This work is a masterful blend of genres rarely seen together: searing family drama, suspenseful crime thriller, and biting social satire. Park Chan-wook has once again proven that he is one of the few living directors in the world who can hold the audience’s pulse and take them to the darkest corners of the human mind, without diminishing the film’s entertainment value one iota. If you missed the madness of Oldboy but want to see a more modern and social narrative, and if you want to see how far a human will go to protect their family, do not miss watching this masterpiece. This is a film that gives a serious warning to us all: the distance between us and becoming a monster is perhaps just one termination letter away.