The Quiet Moment Someone Slips Out of Your Life

It happens more often than we admit. Someone who was present in your life, someone who laughed with you, shared plans with you, replied instantly, showed warmth, interest, or routine familiarity suddenly disappears. They do not answer messages. They do not explain. They simply step out of your world quietly, as if a switch has been turned off. At first glance it feels like disrespect or emotional irresponsibility. But when we look deeper, we find that behind every disappearance lies a complicated inner story; one made of fear, pressure, shame, confusion, or a silent collapse that the person couldn’t put into words.

Humans are social beings, but they are not endlessly available for social life. We tend to imagine that when someone is physically present with us, their emotional capacity is intact. In reality, many people live with an internal conflict that drains them even in the middle of connection. This invisible struggle consumes energy day after day, and eventually arrives a point where the person quietly retreats; not because something happened between you and them, but because something happened inside them. Many disappearances begin not with anger or conflict, but with exhaustion.

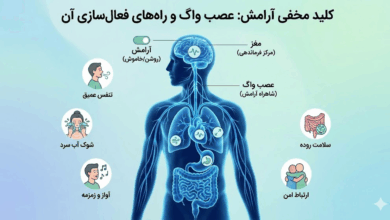

Psychologists call this pattern Social Vanishing. In today’s world, it has become far more common than before. Modern life places individuals under constant social pressure; messages, calls, notifications, expectations, emotional roles, professional roles, online engagement, and the unspoken demand to always be “available.” The mind becomes overloaded. And when a system is overloaded, it shuts down; not explosively, but silently. Withdrawal becomes the brain’s way of protecting itself.

A surprising number of vanishings have roots in shame. Shame about not being able to maintain the idealized version of oneself. Shame about not feeling well but not knowing how to explain it. Shame about becoming emotionally inconsistent. Many people would rather disappear than say something as vulnerable as, I don’t know what’s happening inside me. And because many were never taught how to pause and communicate their limits, they choose the easiest path in the moment: silence.

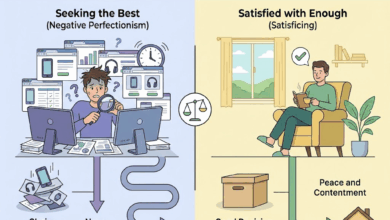

Sociologists argue that this behavior is amplified by extreme individualism. In a culture where “everyone is responsible only for themselves,” cutting ties becomes normalized. But this cultural framing hides a deeper truth: most people who vanish are not confident or indifferent; they are overwhelmed. They are not rejecting others; they are overwhelmed by themselves. And admitting that is far more daunting than leaving silently.

Social vanishing does not occur only in romantic relationships. It shows up in friendships, work collaborations, creative partnerships, family dynamics, and even casual connections. Someone laughs with you, makes plans, checks in, and then disappears without warning. Often the cause has nothing to do with the other person. But because human beings naturally personalize, the one left behind creates a narrative that centers themselves: I must have done something wrong. I wasn’t enough. Something about me pushed them away. Yet the truth is that vanishings are usually reflections of the vanisher’s inner overwhelm, not the abandoned person’s value.

One of the strongest roots of this behavior is poor conflict tolerance. People who grew up without healthy models of communication often find emotional tension unbearable. When confronted with discomfort, they do not speak; they escape. Their mind has learned that disappearing feels safer than confronting, even if it creates harm later. This pattern is rarely conscious. The person themselves often does not understand why they withdraw. They only know they cannot stay.

Interestingly, vanishing is not always permanent. Many people return after a while; quieter, more stable, sometimes regretful. But their return is also wrapped in shame. They fear explaining where they’ve been or why they left. They fear vulnerability even in their apology. So their reappearance is as quiet as their disappearance.

This leads to the question: how should one respond when someone disappears? The most important step is not to take it personally. This does not mean suppressing your feelings; it means recognizing that the cause is rarely about you. Pressuring the person, demanding explanations, or pushing them into a conversation often drives them further away. People who vanish are usually at the edge of their emotional capacity. The most effective response is gentle and non-demanding: Whenever you’re ready, I’m here. The rest must be left to time.

But what if you are the one who sometimes disappears? Then the first step is accepting that needing space is not a flaw. But disappearing entirely can damage relationships. Learning to retreat without erasing yourself is a skill. A single sentence can protect a relationship from unnecessary pain: I need a little space, but I’ll be back. Honest, simple, humane. Silence does not always need to be total.

In the end, social vanishing is a story about the modern human. A person pulled in too many directions, managing too many roles, carrying too many inner burdens. Sometimes the only way they know how to breathe is to step out of the world for a while. The behavior may be hurtful, but it often comes from a mind fighting to survive, not a heart choosing cruelty. And perhaps the quiet lesson in all of this is that people rarely behave exactly as they appear. Behind every disappearance is someone who reached the limit of what their mind could hold.

Sources:

- Emotional Withdrawal and Social Disengagement

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272735822000715 - Avoidant Coping and Emotional Overload

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1088868312452341 - Stress, Social Overload, and Digital Burnout

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0747563221002805 - Attachment Styles and Conflict Avoidance

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0265407519888291 - Shame and Silent Withdrawal (Brené Brown Research)

https://brenebrown.com/articles/2018/05/24/shame-resilience-theory/ - The Psychology of Ghosting (APA)

https://www.apa.org/monitor/2021/01/trends-relationships