A Mind That Injures Itself Before Anything Happens

Catastrophizing is one of the most exhausting habits of the modern mind. Before anything even happens, the brain imagines the worst possible outcome. When someone replies late, we assume they’re upset. A small mistake at work turns into a complete career meltdown in our imagination. The sound of an ambulance in the street becomes the sign of a personal tragedy. But why does the human mind escalate small events into full-scale disasters? Why does this pattern appear everywhere, like a quiet shadow under daily life?

Psychologists argue that catastrophizing is not a sign of weakness but the result of an ancient survival mechanism. Thousands of years ago, the cost of “false alarms” was low, but the cost of missing a real danger was immense. If a human mistook the sound of the wind for a predator, the only consequence was a brief panic. But if they ignored a real predator, the consequence could be death. This bias made the human brain evolve with a rule: better to be scared and wrong than calm and dead. This is the primitive root of catastrophizing.

The problem is that our ancient brain now lives in a symbolic world. The threats we deal with are emotional – job evaluations, relationships, messages, deadlines – not lions in the dark. But the brain cannot tell the difference. When your boss says “come to my office later,” the brain instantly builds a full disaster scenario: job loss, financial collapse, social humiliation. The brain thinks it’s saving your life, while in reality it’s reacting to a simple meeting request.

Research shows that catastrophizing is not imagination but a cognitive bias. The mind naturally magnifies negative signals and ignores neutral or positive ones; a phenomenon called negative bias. A simple “we need to talk” from a partner is interpreted not as conversation, but as a breakup. The mind uses its own script, not the reality in front of it.

Modern society amplifies this bias. A culture driven by speed, competition, comparison, and perfection keeps people in a state of constant alertness. Social media intensifies this sense of inadequacy. Work culture treats even small errors as threats to identity and status. Modern life teaches the mind that “there is always something to lose,” making catastrophizing a default reaction.

What makes catastrophizing even more damaging is that it happens silently. We may look calm from the outside, but inside a full disaster movie is unfolding. And the body reacts to this imaginary film as if it were real; increased heartbeat, sweating, the nervous system entering fight-or-flight mode. The body believes the story even if the event hasn’t happened.

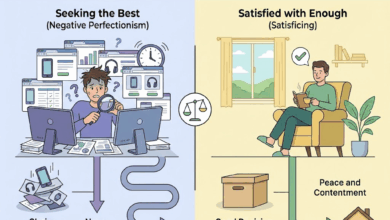

Why do some people catastrophize more than others? Part of the answer lies in personality and early experiences. People who grew up in unpredictable or tense environments are more sensitive to potential danger. Their brains learned early in life that safety is never guaranteed. Perfectionists also catastrophize more, because small mistakes feel like threats to their worth.

Therapists suggest that the first step to reducing catastrophizing is recognizing that the “disaster scenario” is not reality; it’s an interpretation. Cognitive therapy offers three crucial questions:

- Do I have real evidence for this thought?

- Are there other explanations?

- Even if the worst happens, am I truly helpless?

These questions weaken the emotional power of catastrophic thinking. Most of our imagined disasters collapse quickly under real examination.

Another strategy is to interrupt the prediction chain. Catastrophizing usually begins with a small event and leaps into a distant future scenario. If we can stop the chain early – through grounding techniques, mindful breathing, or shifting attention to the body – anxiety drops dramatically.

But the deepest solution might be changing our relationship with uncertainty. A mind that cannot tolerate “not knowing” always chooses the worst scenario because negative certainty feels safer than ambiguity. When we accept that uncertainty is part of life, the mind stops trying to fill the gap with disaster.

Catastrophizing will never disappear completely; it is part of our evolutionary inheritance. But we can learn to slow it down, soften it, and not let it dictate our decisions. A mind that wounds itself before anything happens is trying to protect us. We just need to remind it that the modern world is not the jungle our ancestors survived.

Sources (with links):

Beck, A. & Clark, D. (1997). Anxiety and cognitive biases.

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1997-42880-004

Hirsch, C. & Mathews, A. (2012). A cognitive model of pathological worry.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S000579671100176X