Where the Mind Leaves Itself; and Comes Back Again

Rumination is one of the most familiar experiences of the modern mind; that state where a single thought loops endlessly, revisiting the past, anticipating the future, and pulling us into hours of mental replay. But why does the brain do this? Why does the mind return to the same thought even when we know that thinking more won’t help? Psychologists argue that rumination isn’t a flaw in personality, but an evolutionary mechanism that no longer fits the world we live in.

The human mind evolved to learn from past mistakes and prepare for future threats. In ancient environments, revisiting danger could save a life: re-imagining an animal attack or replaying a tribal conflict increased survival. But in the modern world, most dangers are symbolic; a bad grade, a misunderstood message, an awkward conversation, a work email. The brain, using its old survival machinery, treats small social or emotional events as life-threatening problems, making them impossible to let go.

Researchers describe rumination as the brain’s attempt to regain control. When uncertainty rises, the mind believes that “thinking more” will lead to certainty. But this is like spinning the wheels of a car stuck in mud; the more you spin, the deeper you sink. People replay conversations, rehearse future dialogues, and analyze past moments over and over. The process feels logical, but it only amplifies anxiety.

In cognitive psychology, rumination is considered a root mechanism behind many disorders. Depression flourishes when the mind fixates on past failures; anxiety intensifies when the mind loops through future possibilities. Yet new research shows that even psychologically healthy individuals ruminate; the difference is only in frequency and intensity. The overstimulated world we live in – constant notifications, competition, and social comparison – keeps the mind in a half-threat state, creating the perfect environment for rumination to grow.

Sociologists add another perspective: rumination is also a product of modern culture. In societies where self-worth is tied to performance, people feel compelled to evaluate every small decision repeatedly. Mistakes are interpreted not as natural human experiences, but as flaws in identity. This leads to endless self-monitoring; as if the mind constantly reviews its own behavior, fearing judgment from an invisible audience.

Loneliness makes this cycle stronger. Studies show that people with deep emotional connections experience significantly less rumination. Conversation acts as a release valve; an exit door from the self. But those who feel unheard or unsupported must hold everything inside, turning the mind into an interrogation room.

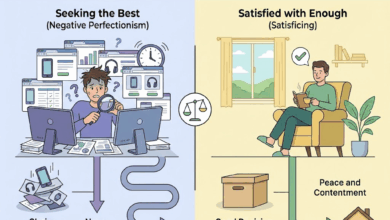

So why do some people ruminate more than others? The answer lies in cognitive style. Analytical thinkers, planners, and future-oriented individuals are more vulnerable. Their strengths in problem-solving become weaknesses when applied to emotional uncertainty. What helps them succeed professionally can harm them emotionally.

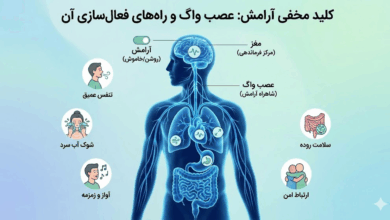

Cognitive-behavioral therapists suggest that breaking the cycle begins with recognizing the trigger; the “hook thought” that starts the loop. Labelling the thought (“This is rumination”) reduces its emotional power. Techniques such as grounding through the five senses, mindful breathing, or shifting to physical action help the brain exit the loop.

From a sociological view, the long-term solution requires reframing our relationship with mistakes. A culture that treats errors as identity defects will always produce anxious, self-monitoring individuals. But environments that normalize imperfection reduce rumination naturally. Deep, supportive relationships also help release mental pressure.

Rumination can’t be removed entirely; the mind will always revisit unresolved issues. But we can learn to make the cycle shorter, gentler, and more humane. A mind that returns to the same thoughts is not broken; it is asking for understanding. With self-kindness and acceptance of human imperfection, we can walk alongside the mind instead of fighting it; until it finally lets go.

Sources with Links:

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms.

https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2000-13301-003

Watkins, E. (2008). Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S000579670700132X