Mental Health on Screen: Why Media Still Gets It Wrong

When the Screen Stays Silent, the Stories Scream

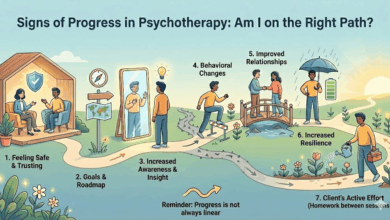

In a world where anxiety, burnout, and emotional struggle have become part of everyday life, the way media portrays mental health still feels out of sync with reality. A new report from the American Psychological Association reveals that despite growing public awareness, film and television continue to simplify, dramatize, or outright distort the realities of mental well-being. The gap between lived experience and its on-screen representation isn’t just aesthetic — it shapes how we, as a society, understand and talk about the mind.

Researchers at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg Inclusion Initiative analyzed the 100 highest-grossing films of 2022. Out of 3,815 major characters, only about 2.1% were depicted as having a mental health condition. That number alone exposes the mismatch between fiction and reality — in real life, roughly one in five adults experiences some form of mental health issue each year. And yet, in film, mental illness remains a rarity, often framed as danger, genius, or tragedy.

The study found that when mental health is depicted, it’s usually extreme — dramatic breakdowns, violent behavior, or artistic suffering. Depression becomes poetic despair, anxiety becomes eccentricity, and psychosis becomes horror. The result is an industry that prizes spectacle over understanding, crafting stories that entertain but rarely heal. As one psychologist quoted in the report put it, “In movies, mental illness either creates a monster or a masterpiece. In real life, it usually creates a human being trying to cope.”

The APA report warns that these portrayals have real consequences. By associating mental illness with danger or instability, media reinforces stigma. Viewers absorb these cues subconsciously, and those who struggle in real life often remain silent — afraid of being judged, labeled, or dismissed. In a culture where visibility shapes validation, this kind of misrepresentation pushes people further into isolation.

Part of the problem lies in how the entertainment industry works. Stories are built on tension, and drama thrives on extremes. That pressure often reduces complex mental realities to a single trope: the tortured genius, the unstable villain, or the fragile victim. But the truth is quieter. Mental health, for most people, isn’t cinematic — it’s routine, subtle, something lived through daily resilience rather than dramatic revelation.

There are, however, signs of change. Shows like BoJack Horseman and Euphoria have tried to approach mental health with nuance and vulnerability, showing characters who are messy but real. Their success suggests that audiences are ready for honesty — they can handle discomfort if it leads to empathy. Still, these exceptions are rare, often born from independent creators rather than studio mandates.

The researchers argue that true progress will require collaboration: writers, directors, and mental health professionals working together. Just as military or legal advisors are now standard on sets, so too should psychological consultants be part of storytelling. Accuracy doesn’t have to mean dullness; it means replacing cliché with connection.

Ultimately, this issue isn’t about correctness but compassion. Every image we consume shapes our collective imagination — of who needs help, who deserves it, and what “normal” even means. When media gets mental health wrong, it doesn’t just misinform us; it silences people who need to be heard. But when it gets it right, it can do something extraordinary: it can make someone watching at home feel less alone.

Source: APA – Psychology and Hollywood: Mental Health