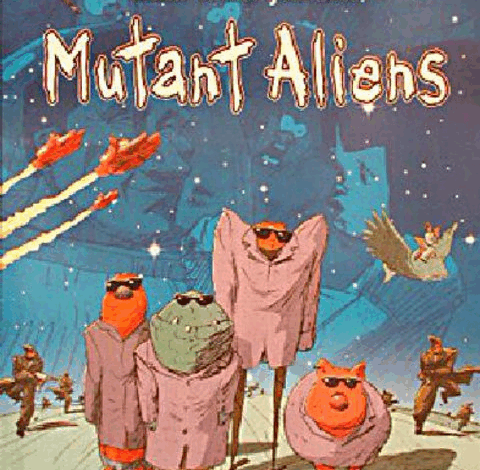

Mutant Aliens

When Desire, Power, and Imagination Become the Same Thing

If Cheatin’ explored love and jealousy as a feverish, sensual dream, Mutant Aliens sends that fever into outer space. This time, Bill Plympton builds a world where lust, power, and imagination are indistinguishable; where every instinct turns into something grotesque, funny, and disturbingly human. It feels like the same mind that once drew two lovers twisting into each other now has drifted away from Earth, carrying its obsessions into orbit.

The film begins with a lone astronaut named Earl Garnet returning to Earth after years lost in space. The media call him a hero, but his own story is much darker: he claims his fellow astronaut betrayed him, leaving him to die, and that he has now returned with a race of “mutant aliens” to take revenge. Garnet’s voice-over is half confession, half delusion, told with a swagger that grows more suspicious the longer he speaks. What starts as a pulp science-fiction adventure slowly mutates into a nightmare of ego, lust, and violence.

Bill Plympton draws every frame himself, just as he always has. The world of Mutant Aliens quivers with hand-drawn imperfection; lines tremble, bodies pulsate, and colors boil like liquid. Everything feels unstable, alive, and vaguely obscene. In this universe, the body is never still: it stretches, melts, and explodes in a constant state of mutation. The style looks simple, but it is deliberate; Plympton wants us to feel that we are not watching a story so much as entering the raw sketchbook of a human mind.

Sex runs through the entire film like an electrical current. Every gesture, every transformation seems charged with erotic energy, but it is not pornographic; it is psychological. In Plympton’s world, sexuality is another form of hunger; a metaphor for control and possession. Even his aliens are strangely human, driven by the same mix of desire and vanity. That is the film’s cruel joke: there are no real aliens here, only reflections of ourselves, warped and amplified.

The humor is dark, absurd, and merciless. Plympton’s visual gags are filthy and philosophical at the same time. A love scene might turn into a massacre; a speech about heroism might collapse into a sexual frenzy. Every laugh catches in your throat. He understands that absurdity and horror are twins — that laughter is often just panic in disguise.

Beneath the chaos, Mutant Aliens is a satire about media, politics, and how easily we turn lies into entertainment. The astronaut’s return becomes a media circus. Reporters and politicians fall over themselves to celebrate his story because it flatters their fantasies: the brave man, the betrayal, the alien menace. No one cares if it is true; they care that it sells. Plympton exposes how craving for spectacle replaces truth; how the audience becomes complicit simply by watching. The film itself becomes a mirror for that addiction.

Psychologically, Mutant Aliens is a portrait of male narcissism; of the way desire and power feed on each other. Garnet’s tale is not really about revenge or survival; it is about being seen. He wants the world to look at him again, to believe he matters. When no one is watching, he invents monsters to make himself interesting. His delusions are both pathetic and universal. Plympton turns that narcissism into cosmic comedy, exaggerating it until it becomes monstrous enough to recognize.

The film’s tone swings wildly between comedy and despair, and its rhythm mirrors that instability. Sound cuts in and out, music shifts from sentimental waltz to mechanical drone. Sometimes the images seem synchronized to the beat of a heartbeat, sometimes they stutter like bad television. Everything feels both handmade and hallucinatory. Plympton edits by instinct, not convention; he cuts when the emotion peaks, not when the plot demands it.

What makes Mutant Aliens so fascinating is that it is simultaneously disgusting and sincere. Beneath all the grotesque eroticism, there is real empathy. Plympton may laugh at human weakness, but he never denies it. His characters — even when they are mutants or caricatures — always ache for something pure. That tension, between mockery and tenderness, gives his work its strange emotional gravity.

When the film premiered at festivals like Annecy and Sundance, reactions were polarized. Some critics hailed it as one of the boldest independent animations of its time; others were repelled by its relentless sexuality and madness. But everyone agreed on one point: no one makes films like Bill Plympton. Variety called it “a fever dream about media, lust, and the madness of the self,” while IndieWire wrote that Plympton “draws what the rest of us repress; and he makes it funny, terrifying, and human all at once.”

Watching Mutant Aliens is a strange experience. You might laugh, then feel uneasy for laughing. You might recoil, then realize the film has simply shown you a part of your own imagination you prefer to forget. It is less about aliens than about the mutations inside us; the way our desires evolve faster than our ethics. By the time Garnet’s story collapses completely, when reality and fantasy become indistinguishable, the film has already delivered its message: we are the mutants. The aliens never came; they were always here, inside the human urge to dominate, to possess, to dream too loudly.

In the end, Mutant Aliens is both hilarious and horrifying, obscene and honest. It reminds us that imagination, lust, and power all spring from the same source, and that art’s job is not to separate them but to expose the mess they make together. Bill Plympton does this without apology, one trembling line at a time; and that is exactly why his films, for all their madness, feel more human than most live-action cinema ever could.